My best friend, Marnie, once told me about a Christmas she'd had with her extended family. The members of Marnie's family are, mostly, country people with down-to-earth ways. I met Marnie at university in 1975, when we were both eighteen, our birthdays only five days apart. I think it was during my first university holidays that I headed off to Dubbo, in NSW, to stay for a week or so with the Johnston's.

Having been brought up in an intensely private family, due to my father's schizophrenia, I loved spending time in more down-to-earth, knockabout families, in which every little facial expression or nuance wasn't examined by my mother (who might decide to exclude someone for days), or my father (who might whack or accuse you of conspiring with Communists or "the man who scraped the paint off the roof").

It was my newly-acquired boyfriend who drove me the 360kms to Dubbo. He returned the next weekend to pick me up again. I wonder if I was grateful? Possibly not. Here is a picture (a phone photo of a photo) of us standing out the front of the Johnston house...

(I made that dress from a bridesmaid's dress that I wore when I was fifteen...)

Marnie's mum took to me, and I really liked her. Marnie told me how they used to stand around the piano while her mum bashed out tunes, and they'd sing the night away. Marnie's dad trained pacers and was the local butcher. There is another poorly-reproduced photo of us looking cool at the Dubbo pool...

That's Marnie on the left and me on the right.

Over the years, Marnie and I have remained close friends. We seem to catch up every couple of years or so.

So... there was this conversation we had about Marnie's family Christmas...

"After we all had lunch, the men disappeared, and the women all went out to the kitchen to wash up and dry the dishes, and talk about all the dead babies..." Marnie had said

.

That was the phrase that struck me: all the dead babies...

Margaret's aunties and sisters and nieces had congregated in the hot kitchen on Christmas day to somehow bring to mind, tell the stories of, and honour all the dead babies: the miscarriages, teenage pregnancies, stillbirths, no doubt some abortions, adoptions, child deaths, infertility...all the terrible tragedies that women carry silently throughout their lives.

Over the past twenty-four hours, something has occurred in my life that brought the phrase- all the dead babies- back to me, and, no! it wasn't a death, but a reminder of the pathos that runs deep through women's stories.

One of my favourite books ever is "Cross Creek", written by Marjorie Kinnan-Rawlings. She was the author of "The Yearling", which is more well-known. "Cross Creek" is based on the real story of the author's move to Florida in the 1920's to an out-of-the way creek surrounded by orange orchards, magnolia trees and hammock (swampy land). True to her era, the writer employs young African-American girls to train-up as maids in her home, and she uses the now-forbidden word for indentured slaves. However, we are all a product of our times.

There is a chapter in Cross Creek that reminds me of this tragic thread that runs through women's lives, and the way our lives are shaped around it, as though tragedy is the woof, and our lives the weave.

"I have used a factual background for most of my tales, and of

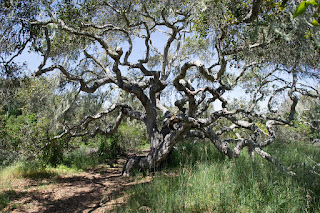

actual people a blend of the true and the imagined. I myself

cannot quite tell where the one ends and the other begins. But I

do remember first a place and then a woman, that stabbed me to

the core, so that I shall never get over the wound of them.

The place was near the village on the Creek road, and I

thought when I saw it that it was a place where children had been

playing. A space under a great spreading live oak had been lived

in. The sand was trodden smooth and there were a decrepit iron

stove and a clothes line, on which a bit of tattered cloth still

hung. There were boxes and a rough table, as though little girls

had been playing house. Only opened tin cans and a rusty pot, I

think, made me inquire about it, for children were not likely to

carry a game so far. I was told that a man and woman, very young,

had lived there for a part of one summer, coming from none knew

where, and going away again with sacks over their shoulders when

the autumn frosts came in.

What manner of man and women could this be, making a home

under an oak tree like some pair of woods animals? Were they

savage outlaws? People who might more profitably be in jail? I

had no way of knowing. The Florida back country was new and

beautiful but of the people I knew nothing. The wild home at the

edge of the woods haunted me. I made pictures to myself of the

man and woman, very young, who had come and gone. Somehow I knew

that they would be not fierce, but gentle. I took up my own life

at the Creek.

The answer to my wonderings was on my own grove and for a long

time I did not know that it was there..."

It turns out that the makeshift tree-home was where the author's "groundsman", Tim, had lived with young his wife. They had taken the job on the grove because of the impending birth of their young infant, but were soon keen to move back to the tree, and autonomy:

"...I only takened this on account o' the

baby comin'. A woman's got to have a roof over her then. Us'll

git along better thouten no house, pertickler jest a piece of a

house like this un here. In the woods, you kin make a smudge to

keep off the skeeters. Us'll make out."

They moved on, the proud angry man and the small tawny lovely

woman and the baby. But they put a mark on me. The woman came to

me in my dreams and tormented me. As I came to know her kind, in

the scrub, the hammock and the piney-woods, I knew that it was a

woman much like her who had made a home under the live oak. The

only way I could shake free of her was to write of her, and she

was Florry in Jacob's Ladder. She still clung to me and

she was Allie in Golden Apples. Now I know that she will

haunt me as long as I live, and all the writing in the world will

not put away the memory of her face and the sound of her

voice.

(The live oak, Quercus virginiana, is named "live" because it is an evergreen oak rather than a deciduous tree as most oaks are).

It seems that this sense of tragedy was something that I learned young. Mrs Regan was a lady with long red hair, and with many children, who lived across the road from us in Blacktown. My big sister used to spend time with the eldest- Anne- and I sometimes played with Janie. I did not know what it was that Mrs Regan died from, but what I imagined, from what I'd heard, was that she had died on a blood-soaked mattress. Was that derived from something I'd overheard? I think it must have been...The thought of this neighbour dying in a pool of blood haunted me. Eventually, the husband remarried and had another tribe of children with a new wife, whose blond-haired children were cossetted, while the first Mrs Regan's children were neglected.

My own mother's three miscarriages, between our big sister and my older brother, also overshadowed our lives. My mother, still in her twenties and living in the backblocks of the western suburbs of Sydney (Quakers' Hill), would confide in my sister, whenever she thought she was pregnant. As an adult who never had children of her own, having spent the years from fourteen and forty-six in the convent, my sister had a phobia of "little things that should be big". I had a theory that her phobia originated in this early over-sharing from my mother. At the age of about eighty, my mother created a tiny rose garden as a memorial to the lost babies, which proves that getting over a miscarriage can result in more enduring grief that is usually acknowledged.

(We had this picture in the hallway when I was a child.)

Like Marjorie Kinnan-Rawlings, I have, throughout different times in my life, found myself haunted by female tragedy. Why female tragedy? Surely there is also enough male tragedy in the world to weigh a person down? I think it's because of the hidden, unspoken-of nature of the tragedies that are exclusively female... It seems that, with each of these narratives, a piece of my woman-soul has been scarred...

When I was a young woman, about to have my first child, an "older" woman (she was possibly merely thirty-five) had told me about a young woman she had come across when she was working as a Social Worker in the town where my husband and I lived. It was in the outskirts of a suburb, where the fibro (asbestos) houses were all on five-acre blocks of dead grass, bony horses and prickly-pear. Perhaps I had mentioned my interest in home-births to the other woman, in passing, although I had booked in to the local hospital, had done Lamaze classes and planned a "le Boyer" birth. Anyway, the older women had told me about the other young woman who had wanted a home-birth, but that her baby had been delivered in some shed on the doctor's land, and she had ended up "badly butchered" (to use her phrasing).

For years, the memory of that girl had haunted me. I tried to work out where the shed might have been, and, if we ever went anywhere in my husband's car, I'd check out the sheds squatting derelict in abandoned paddocks. I did not know, back then, that that kind of obsessiveness would lead me to become a writer, 'though I sometimes sat in the shade of the house, on lonely summer afternoons, writing poems, while my baby girl slept in her pram.

Years later- it would have been about twelve years later- I started taking photographs of the old sheds in the Huon Valley, in Tasmania, possibly forgetting my obsession with that original shed back in Blacktown.

It's most likely that, subconsciously, I did remember that shed, as I started writing a novel to my sister-in-law who had committed suicide, interspersing the novel with the photos of the sheds. I had originally named it "Empty Sheds in Empty Paddocks", but eventually changed the title to "The Spinning Game". It was a novel about the ritual sacrifice of girls and young women.

I was talking to Marnie just last night, as I had shared an amazing discovery with her (which will follow shortly). She understood my obsession with the "tragedy" that we shared, as 18-year-olds, and she mentioned a Greek boy who had attended her primary school for only one year, and of how she and her friends from her childhood home-town would mention him whenever they came together. "I wonder whatever happened to xxx?" they would muse.

It was a similar story with "Erica Scholz" (name changed). Erica was a girl who had arrived at university from a country Catholic school, where she had been the school captain. By accounts, her family was strict and religious. Erica lost the plot over that first year, and we would laugh when she arrived late at lectures, one day arriving ten minutes after the lecture had finished. I remember her so clearly, as she was the sort of girl I wished I was: dark-haired, pretty, soft-looking, shorter than me...what I imagined a DH Lawrence character might look like. (I was tall, skinny, freckly...and felt "gawky"...).

Inevitably, Erica got herself a boyfriend and, basically, spent that whole year besotted and infatuated. Also, inevitably, she ended up pregnant. She suddenly disappeared from university and the story was that her "strict" parents had made her return to the country town, change her name, and give her baby up for adoption. Thus, over the years, Marnie and I have often referred to Erica. We wondered where she was, and how her life had turned out. I even went to the length of searching for her on Facebook, finding someone with her name and discovering that that Erica Scholtz lived in Germany.

For some reason, I could not let it rest, so that, a few months ago, I contacted the Historical Society in Erica's hometown (yes, I remembered it, 45 years later...). To cut a long story a bit shorter, I did track Erica down, and, in the middle of the night a few weeks ago, I received a message from her.

I cannot explain the impact this has had on me. Erica told me that she had reunited with her son when he was eighteen, and had two beautiful children from her marriage. I was so emotional. I cried for days, especially when I attempted to tell someone the story. They were, understandably, perplexed. Marnie, however, understood. She realised what a shadow Erica's story had cast over us, as young women.

My eldest daughter, aged 41, pointed something out to me, when I told her the story. I, too, became pregnant, but it was in my last year at university. On my first visit to the family doctor, his first question was: "Will you have your baby adopted?" I was in a committed relationship. We had decided to get married. Of course, I was going to keep my baby! I think that was, deep down, why Erica's situation cut so close to the bone. It could have been me...

My first child, Heidi, aged about 18 months...

Heidi with her son, Leo...